|

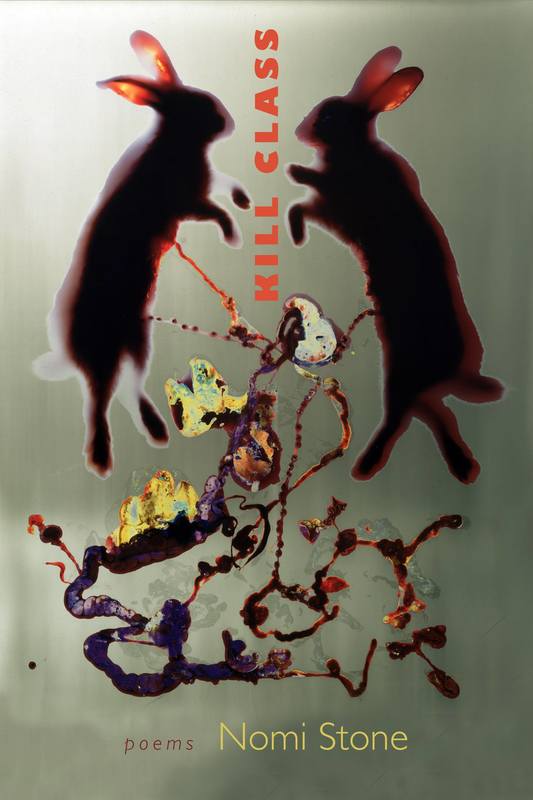

Kill Class by Nomi Stone (Tupelo Press, 2019)

They call it the kill zone I am going deeper in We haven’t slept Pollen burns my nose When shot in the head or torso at close range, die-in-place and no steak dinner (from “The Notionally Dead”) What does it feel like to be an anthropologist observing the roots and cores of the United States Military Industrial Complex? What is the experience of roleplaying and becoming and maintaining “the other” in real, professional war games simulating the Middle East in the American South? These are questions examined by Nomi Stone’s speaker in Kill Class, a book of poems that is emotionally uproarious, intellectually chaotic, and filled with a torpor of spirituality in a landscape of displaced humanism and degraded identity. This book, Stone’s second and a follow up to 2008’s Stranger’s Notebook, blends Stone’s numerous skills into a single, defiant statement that demands a revisiting to our seemingly-endless production of conflict. The world of Kill Class is a fully-realized, fictionalized version of real places that are not so far from where you are. From where we all are. “’Pineland [is] a simulated country in the woods of the American South, where individuals of Middle Eastern origin are hired to perform in a theatricalized war, repetitively pretending to bargain and mourn and die” describes the context of this space of horror and the horrific. Pineland is also where we find the poet-anthropologist, one or many or universally all, who each bring their identity into this space of flux and cruel juxtapositions. The speaker moves in and out of the scenarios and situations, in and out of the role that has been provided, the back story and the vague sense of realism and wholeness. Stone’s writing doesn’t afford comfort and the shattered mirrors are painfully present. The voices in this book are slanted and fractured, collective but damaged, broken, and paralytic to the point of a wretched, damning beauty. We go. I can’t keep up with the group. Gypsy you stay right behind me Everything will be all right. I try to make small talk because other talk brings me out / you have to stay in. (from “Kill Class”) It is educational to be part of Pineland as it is to document the experience. As it is to read through the documentation and fragments of stories and the singular narrative that does repeat, and repeat, and challenge in its repetitions. Stone’s resultant book (these poems) gruesomely represents the repetition of any given program, military or otherwise, and the endurance of rote pressure. The most antagonistic spaces of Stone’s narrative are when superiors, positions of authority and/or masculine encroachment, attempt to undermine the speaker’s voice and individuality. It is part of the war game and war games are indicative of war, systemic or personal. Stone’s speakers are strong but face conflict, of the other actors within Pineland and of the self, almost incessantly. This truth, that Stone lived through and engaged for two years the work to not only exist but to persist is heroic; and yet despite the success of the documented words, the poems, there is a very distinct, shadow side of this book. Does anyone have a translation for any of this? If your face is a mirror (depending on whom you face), behind you is a splinter. This is one proverb (from “Living the Role”) That shadow is also one of the strongest metaphors operating throughout Kill Class, and it is also one of the major activities for the speakers in the poems: translation. Translation appears in many forms. The speaker translates phrases and terms between Arabic and English. For example, the quote above is based on the Iraqi proverb “If your face is a mirror and the back of your head a splinter” and its presence emphasizes boundaries, distances, and communion. The speaker translates these cultural junctions of Middle Eastern countries through the tragic contextual spaces of the contemporary American war game. Translation is also inclusive of the necessary act of independence. It is the documented experience. The speakers as both ethnographers and artists translate through concise, spirited response. This translation of experience appears a means of survival and emotional stability. It comes in the form of the direct notes from points in the simulated exercise to the documented modes of freedom when the day’s acting is over, and re-entry occurs through the appearance of strip-mall (and its fast food symbolism) and the intimately-welcoming small-town pub. There is a door in every word; behind it, someone grieving. (from “War Game: America”) Like so much poetry that has existed before and will continue to appear, the poetry of Kill Class represents this process of translation as one that is a continuum, and a presence. While translation serves as an empathetic counterpoint to the sickening simulation of Pineland, translation is also the shadow of Pineland’s overall story. The people who make up the experiences in these sad, ongoing circumstances become more human through each poem, each practice, each situation. Their fictionalized experiences and lives are humanized through documentation and the value of the written word. It is sad that as they are discovered and described, so too is the pain and the conflict of their existence. And so too the pain and the conflict of the separation between the reader, the author, and between these individuals who exist out there, somewhere, and have real names and fully human lives. Stone’s book may be a political act in its existence. It may exist to serve as a reminder that the American world of war is hidden behind curtains, between threads, and around corners. It may be an extension of conversations that have occurred for decades. And yet its heaviness, its provocation, its urgency exists in a solemn and chiseled authorial vision. Kill Class has transcribed as openly as possible the experiences of Pineland, as well as the personal experiences and stories of the poet-anthropologist. As such the weight of its existence may be more strongly felt, but it also it maintains an integrity of interpretation. As with stepping into a forest or an unknown, vast space for the first time, the prerogative the book brings reflects what the reader brings into it. The dynamic between the book and the reader may be the source of horror and the horrific that lurks from the first page. [. . .] The woods are a class in what they can take. The country is fat. We eat from its side. (from “War Catalogues”)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Welcome to Yellow Rabbits. Thanks for visiting.

All reviews by Greg Bem unless marked otherwise.

SearchYellow Rabbits Reviews

Archives by Month

August 2019

|