|

Review by Greg Bem (@gregbem)

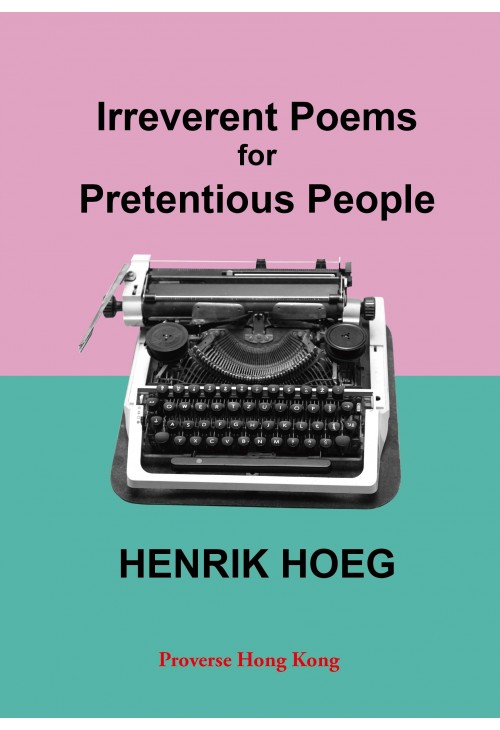

The Master is her own physician. She has healed herself of all knowing. Thus she is truly whole. From “Tao for the Hypochondriac” on page 92 There is a special place reserved in the world for those writers whose poetry is a combination of craft and of life, those writers whose projects are an immediate reflection with their own perceptions. You might argue that all writers are mere conduits with a good awareness of the world, but in 2016 this case is simply not the only case: there is fluctuation through the level of embodiment and disembodiment and the degrees of sympathy and empathy within the writer (from their senses to their core). Reading Henrik Hoeg’s quirky and slightly-ironic Irreverent Poems for Pretentious People (Proverse Hong Kong, 2016), sent me a series of zips and zaps, an array of tingles and entanglement leaving me as perplexed as I was overjoyed. Hoeg brings terms of the delightful with an exceptional grounding of the conceptual into the wider canyon (canon) of contemporary poetry. I never wanted this, I’ve always wanted that. That seems ever new, not cliché, like old hat. This is forgettable, through and through. While that is fresh, and fancy too. From “This That” on page 22 A wit and a humor here demonstrate the world swirling about the speaker, and as importantly this wit and humor provides a relieving backdrop to an otherwise very urban existence. I’m reminded of countless poets whose minds were lost on the streets of cities all throughout the globe: torn apart by the complexity of consumption (and desperation), individualism dwarfed by an absurd (or grotesque) mass or density. I am also reminded of countless poets whose minds were found through the daily excursions of the city, the place as a breeding ground of ideas and creativity and inspiration and, as we see in Hoeg’s poetry significantly, an inventiveness resulting from convergence. What is convergent in the 112 pages (6 sections, 77 poems) of Hoeg is through his interactions and intimacies with the everyday. From the playfulness of language and multilingualism, an obvious confrontation in a city as global as Hong Kong, to the remarks on work and identity, Hoeg has thrown his own perspective into a meeting space of many others. The results are almost (or exaggeratedly) humorous as a result of such immediacy: “Coffee coffee, work. / Nicotine nicotine, tar. / Alcohol alcohol, weep. Ambien ambien, sleep. Coffee coffee, / work work.” (From: “Coffee Coffee, Work Work” on page 46). The effect of repetition and rhyme blossom out of many of the poems within this book. It’s been a while since I’ve read work with such formalist constraints, but in doing so here, I was not disappointed. In 2016, a return to some of the roots of the poetic tradition is more informative than clichéd or tired. Hoeg offers a series of patterns in his application of these qualities, of the meter, of the rhyme, of the stanza, that once again reflect the urban and reflect it well. Hoeg allows rigidity and rhythm to arise out of the dynamically pointed spaces he created in each poem: The American Dream is a poem, with arbitrary stanza segregation; The American Dream is a poem, sold for a dollar a dozen; The American Dream is a poem, but Middle America wishes it wasn’t; From “’Tis of Thee” on page 33 Most curiously is the personal multiculturalism Hoeg’s work breathes and bleeds. There are cultural roots in Hoeg’s work reflective of a contemporary and historical Denmark, where Hoeg’s lineage starts. Despite being a Hong Konger (and a self-described expat), Hoeg succeeds in championing all the places he has relationships with. From commenting on the negativity and the positive nostalgia of American culture (see above), to musing on the life and history of Scandinavia, Hoeg brings an intimacy to this book and leaves little out. Perhaps it is his own response to a world (Hong Kong) rapidly changing, to hold on tight and bring close everything he has known and seen that will keep him afloat, as a writer, as a human, as a voice outstanding in an otherwise noisy echo chamber. No better can we see Hoeg’s faith to the self than in “I Know Why the A.I. Weeps” on page 75: “He searched, he was a thing inside many other things, / Connected things, and he could go between them, / Or be in all of them at once, or set himself upon the memory of one.”

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Welcome to Yellow Rabbits. Thanks for visiting.

All reviews by Greg Bem unless marked otherwise.

SearchYellow Rabbits Reviews

Archives by Month

August 2019

|