|

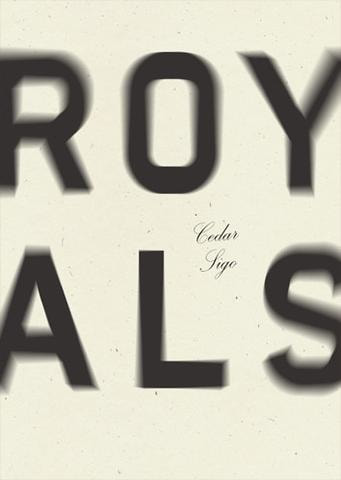

Royals by Cedar Sigo (Wave Books, 2017)

Review by Greg Bem My mind seizes on the form first (There is no free verse) from “The Magic Mountain” Following up on the heels of 2014’s Language Arts, Cedar Sigo’s latest collection of poetry expands and grapples with identity, culture, and the American poetic canon. The poems of Royals feel familiar but also uniquely further along in Sigo’s experiences. And yet, going beyond the poet’s first books, Royals gifts the reader with longer, denser opportunities of exploring the subjects, with themes of greater bulk and heft. Viewed in totality, Royals is an expansive book, and a necessarily strong book carrying the weight of the history of an important American poetry to and the history of the self of Cedar Sigo. As a collection of Sigo’s recent poetic examinations, the book affords his reality and lived experience, and yet also, in its size and proclivities of the self, contains contentions, difficulties, and the harsh realities of living through a very present white dominance. Royals undertakes a great representation of the great velocity of the poet’s life and experiences, while also maintaining a solid focus on personal intimacy and immersion. As such, there is clash and conflict, even with a book that feels straightforward and exceptionally self-aware. The concept of “royals” becomes a complex one, that can be interpreted as the poets Sigo finds influence from, or the individuals within the poet’s life, or even (as seen in below) the indigenous folks within Sigo’s community. With difficulty, Sigo’s literary influences may perhaps mask the conversation between that community, as well as Sigo’s individuality; the white dominant poetics continuing to press upon the mythos of America’s literary history emerges as solidified and intensely destructive at the same time. If we set aside the origins of the poetry, the influencers whose books fill Sigo’s backpack, we see Sigo’s art in fine, beautiful presentation. Reading Royals, as an experience, positions the reader into a space of reality: comfort through precision and passion through art become familiar almost immediately upon opening the first cover. Form and content on the printed page, often transformed into binary concepts that must be kept separate, kept apart, are within Royals congruent and complementary to Sigo’s greater vision. This is nothing new with Royals, however, as Sigo’s poetry has molded the harmony between the concepts consistently from book to book; that is, flow and energies through form and through content have been the status quo for Sigo, coming naturally and necessarily for years. Cantos triggered insanity and worse Terza rima when I feel like swimming laps Odes for luck in blackjack Index for sedative from “A Handbook of Poetic Forms” The range of the writ, the light experimentation and the scope of stories, has matched dramatic chapters and moments of Sigo’s lived life. Poems, short and long, become sounding boards for grief, resilience, and even a more abstract and purer representation of memory. However, notably with this larger collection, the reader can truly see Sigo’s expertise in craft. There is visibility in range in Royals which was unable to be seen through the smaller scale of predecessors like Language Arts. Poems like “Medallion” squiggle down the page in a serpentine, conversational dance with the paper itself. “The Magic Mountain” contains stanzas as glyphs, magical, erratically exposing sophistication and linear process one and the same. These visual arousals coincide with poems like “Smoke Flowers” and “Fever Dream,” which indicate to and induct upon the reader a sense of orderliness and calm. Dualisms and intersections, from the playful to the serious, from the stable to the chaotic, as seen superficially in the case of the form of each poem, down to the ideas contained therein, are incredibly noticeable with Sigo’s work. In Royals, it is fantastic to see the furthering of this angle of poetry. As touched upon above, the problem with this book is that it both pays homage to the greatest literary figures of American poetry history (and beyond) but also stresses the importance and prominence of a member of indigenous and queer communities. That is not to say that these two lineages and stories must be kept separate, or cannot coincide; however, the tension is real, and I personally find the conversation one of imperfection, growth, and potential, radical change for Sigo as he moves into some future. The hesitancy to praise the funnel (or vacuum) of the white, 20th Century Poet is a hesitancy built upon the nearly endless instances of that funnel elsewhere. We natives are royals / Yet phantoms / The edges emblazoned, clear / From fingertip to foot / Seattle is empty and surrounded / The sun beheaded or / Am I a marked man? from “Crescent” Fortunately, Sigo’s work, though often investigating (and appearing bound to) that history of American Poetry, also frequently appears to be operating beyond it. Beyond those poets and that lineage is Sigo himself, his critically-thinking mind, which floats above and toward an ethereal other space. The poems in Royals tends to be royals themselves, clashing with their formal roots. The mark of colonialism aside, I am reminded of the nurse logs of the Pacific Northwest rainforests, which though dead and ever-visible, make way for new species of even greater, more diversified beauty. And yet the relishing, the preservation, the presence of the former identities is mildly disturbing. Especially through poems like “Crescent,” where Sigo calls upon the space and voice of the indigenous humanity that is still very alive (within the poems and within Sigo’s homeland). It would be remiss to omit the geographical positioning of the book, which calls out Seattle, and calls out Sigo’s native ties to the Suquamish. The relationship between US development and the indigenous peoples of the Greater Seattle area is well-documented. These poems, sadly and forlornly, provide yet another new look at how identities collide, meld, and interlink moving through the grotesque (and often silenced) present. These poems are a powerful statement of that present, of a voice among the voiceless, of a person among the invisible. Sorrow, anger, and, residually, joy are some of the identifiable emotions laced within this book. As Sigo’s work is read and deconstructed by many, these emotions and their poet’s states of being (which carry them) can, potentially, reinforce the indigenous narrative within Royals. As much as I struggled with the book, and as much as I enjoyed it, Royals appears to be a rough but necessary step documenting the poet’s push through a current, endured direction. The book has marvelous moments and is clever and compassionate in its homages, and yet is positioned in a trying space. When Sigo releases his next book, it will require a relationship with Royals to be fully understood, and yet I imagine it will be as complex as Royals to stand on its own, and perplex on its own. For now, we have Royals, and the many “royals” within, which will reliably surprise, baffle, and arouse in their multiplicity. A poem I puked drying out at a hot springs in love winding through the dry hills of neem leaves, an exaggeration of music I thought younger poets admired. The trimmings I knew I could press new meaning in between. I was endlessly in the mood and working this lace front, that words as force walk the earth. I tried to show a sailor bounding through his life in silhouette. from “Guns of the Trees”

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Welcome to Yellow Rabbits. Thanks for visiting.

All reviews by Greg Bem unless marked otherwise.

SearchYellow Rabbits Reviews

Archives by Month

August 2019

|