|

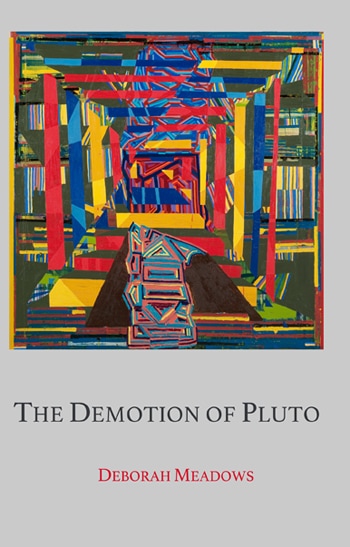

The Demotion of Pluto: Poems and Plays by Deborah Meadows (Released by BlazeVOX Books, 2017)

Review by Greg Bem (@gregbem) Poetry capable of elevating the reader into new ways of thinking about language often runs the risk of isolating and ostracizing the reader through challenge and difficulty in the breakage of paradigms. At the same time, buffering the reader and easing them into a difficult work often requires a diffusion of ideas through an accessibility of experimentation and transparent conceptualization. Doing so often risks compromising works that are intellectually evolved and wall themselves up. In Deborah Meadows’s latest collection of writing, The Demotion of Pluto: Poems and Plays, these fine lines are approached and often transcended through the poet’s consistent use of external influences and forces. Her book here, like many of her previous works, erupts through lineages, borrowing tokens from other authors and thinkers contemporary, historical, and ancient. This meshing and mixing produces positive results that transform The Demotion into far more than a “difficult book,” allowing for rewards simply for sitting through the turbulence of the reading experience. Buck Euro: Some of that ugly, the stink, that trauma: it really makes me sick. That’s why we need a story. We get involved, forget our woes, feel transport. (from “The Demotion of Pluto” on page 54) As identified and fortified in her previous book of 2013, Translation—the bass accompaniment: Selected Poems, Meadows harkens on an explosive set of influences to inform her work, similar to the recent “handholding” work of Tracie Morris, to name one example. Rather than list all of her previous influencers and collaborators here, I will simply list the cast of characters in the 47-page title play of The Demotion: Philoctetes, Neoptolemus, Odysseus, Ghost of Fox, Anonymous Endangered Fisher, Cosmonaut Sergei Rikalev, HAM operator Margaret Laquinto, Lorine Niedecker, Louis Zukofsky, Buck Euro, Dark Imagebase, and Leo and Hercules (two chimpanzees). As one might assume through the literary nature of these characters, Meadows pulls direct allusions and greater, loftier symbolic meaning through contemporary interpretations. Like the best drama, characters represent more than themselves, and Meadows sufficiently explores representation as both denotation (historical) and connotation (adaptive) in her own context. Bordering on themes of entertainment, absurdity, and critical inquiry, Meadows’s play, like her other dramatic works, is not quite content in any single space of poetic intention. The play is like the book, as a whole, which demonstrates the blending and breaking of particularities and satisfactions. In the context of the artist and the artist’s creations there is a defying of genre. In “The Demotion” there is often verse, most likely functioning with an element of grandiose subtext, embedded into otherwise cryptic but casual, prosaic dialogue and monologue—think Shakespeare, to name the biggest example. As a connector to the reader, moments like this, moments of creeping beauty, are what Meadows’s does best—that is, the works in this book are filled with surprise and delight amidst sometimes-confusing narrative and context that goes beyond the borders of reader expectation and normalcy. Keeping the story from appearing straightforward and the context from becoming identified is what arouses a degree of mystery within The Demotion. In a later dramatic piece, the very-much-meta “The Obstacle Plays,” Meadows provides a sequence of scenes of two sisters, Kinsan-G and Fetch, along with an otherly old man named Clamp. Philosophical and situational, each scene is like a new experiment or proposed idea framed in exclusive dialogue. Clamp as the other allows for subtle and direct levels of feminism to be cast outward with his sense of existing as a target, and while the exact commentary in these situations remains humble or covert, Meadows’s at the least provides a platform for inquiry. Reading “The Obstacle Plays” resulted in me thinking of Meadows working through her own mind as she wrote the play out—there was a breakage from complete immersion here, as with most of her works. The book contains one additional play, “Nothing to Do,” which reads like a sitcom or a sketch—two characters, Jay and Adelaine, speak over the course of several pages in a setting “neither domestic nor institutional,” and though not canon-shattering, the work is potent and pronounced, memorable yet unexaggerated. I am reminded of American Splendor, or Coffee and Cigarettes. One might wonder how such a piece would translate into a stage performance, or a video form. And of course, it would be in error to not mention Meadows’s previously-established commitments to collaboration, adaptation, and evolution of her works into other spaces with other artists, thus representing a dynamic multidirectional trail of influence. all of us are here: same space, same decay (from “when body is earth yet to cover” on page 58) In some of the poems that Meadows’s provides in The Demotion, the larger philosophies and part of that grandiose subtext previously mentioned, which I can’t help but describe as a humanistic drive, leak out like secrets being exposed. As I made note again and again, the poems here are very inquisitive, and give off tones of active, not reactive, searching. The larger motifs that cross works here, binding them together a la “the book,” include the meaning behind authenticity, integrity, functionality, and responsibility. From the displacement of the characters in her plays to her own multitude of voices, to even the final sequence of poems in the book that decay out of their selves, Meadows provides blunt statements, often nihilistic, often existential, on why we are who we are and what we are supposed to realize and then give back to the world. Not quite depressing but certainly uncomfortable, these notions of existence and purpose in Meadows’s most poetic moments are in many cases the most straightforward moments in otherwise mysterious works. down here adhere (smoke to wet paint) routine (to glass pane) cradled strangled ("modesty” on page 122) Still, it is a challenge to define Meadows’s work in The Demotion in any singular way, which is partly why this book shines so brightly. In some of the later poems, there is a quality that is less static and direct, with subconscious, sub-present explorations of reactions to world events (political, environmental) and an almost spontaneous sense of poetic existence. “Medium Logic Machines” reads like a cross between William Burroughs and Joanne Kyger. “Slang of Regime Deferral” reads like Michael Gizzi. There is a sense of play here, and it is rooted in an intensity that much of contemporary poetry lacks. Said playful intensity reminds me of Keats’s negative capability, and reminds me of Stein’s exceptional linguistic topsy-turvy directives. Would this book benefit from having greater explanations about each of the works? Probably. But would something be lost through a closer and more explicit explanation? Definitely. Meadows’s work before The Demotion and through The Demotion maintains Ezra Pound’s “make it new” in 2017 better than most other writers I’ve read, and yet in an age where more and more content is accessible and more and more content is designed to flow “correctly” and succinctly, the idea of “newness” both within literary art and beyond feels counterintuitive. That said, these works by Meadows certainly have their own place, their own spirit, and in so respond to Meadows’s fascinating commentary on the certainty of functionality and responsibility in society—by being certainly functional and responsible and yet not completely definable.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Welcome to Yellow Rabbits. Thanks for visiting.

All reviews by Greg Bem unless marked otherwise.

SearchYellow Rabbits Reviews

Archives by Month

August 2019

|