|

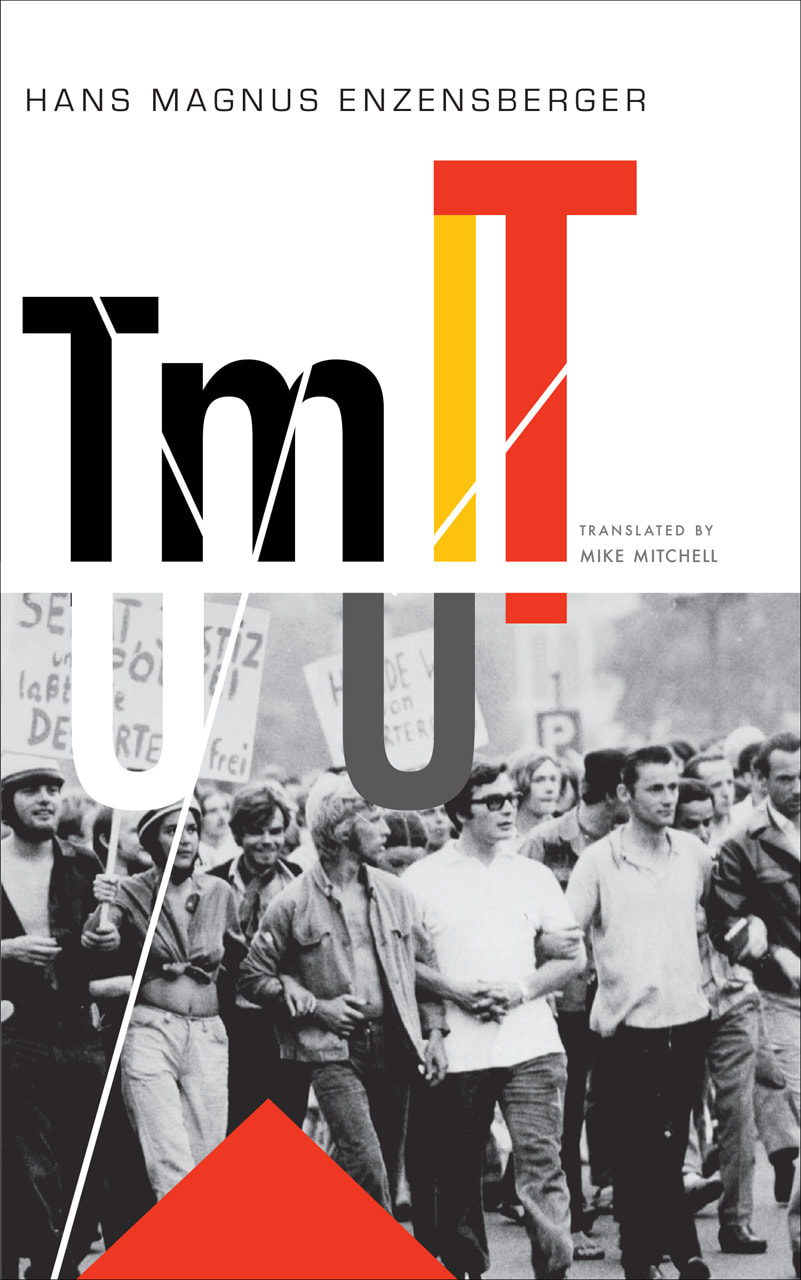

Tumult by Hans Magnus Enzensberger (Seagull Books, 2016)

Review by Greg Bem (@gregbem) On the periphery: Voices of Dust by Demdike Stare I drink my tea, close the door behind me and rub the sleep out of my eyes. A girl in rags and tatters is waiting for me outside between two Cadillacs. We walk to the bus stop. Each of us puts five centavos in the payment box. The journey lasts three-quarters of an hour. We get off in one of the suburbs. It’s still pitch dark, the streets are deserted. We make our way through rubbish, banana plants and goats tethered to a water tower. We ask an old peasant who’s squatting there, ‘Where are the writers?’ His only answer is a vague wave of the hand. From Memories of a Tumult (1967-1970) How to make sense of the precision between the glory and the monotony of the bounty and retraction of life within a given historical period? Within a scope of complexity? How to promote significance while also acknowledging the meandering breakdown of one’s textured ebbs and flows of the everyday? One approach is through craft, like a slow, chiseled piece of material: slowly, methodically, and through the intimacy of the relationships with individuals. Another method: the testing of the material across time, across length, across a body, liquidous, filled with the urgency of semi-identifiable forces. These qualities are uproarious in the context of the global middle of the twentieth century, politically and economically and culturally and geographically, and in Tumult, revered poet, poignant leftist, and ambitious traveler Hans Magnus Enzensberger finds a foothold in his own life to explain the lives of so many others. The book in question follows the form of layers: a book that is divided into five major works, Notes on a First Encounter with Russia, Scribbled Diary Notes from a Trip Around the Soviet Union and Its Consequences, Premises, Memories of a Tumult, and Thereafter. All translated from German into a furtive English by the award-winning Mike Mitchell, these works take the author’s autobiographical journeys and bridge (or triangulate) them through many chapters of his significant relationship with Maria Alexandrovna Enzensberger (“Masha”), which carry the weight of a self-proclaimed Russian novel. However, my interest in writing an autobiography leaves something to be desired. I absolutely have no wish to make a mental note of everything that happens to me. It is with reluctance that I leaf through the memoirs of my contemporaries. I don’t trust them one inch. You don’t have to be a criminologist or an epistemologist to know that you can’t rely on people’s testimonies on their own behalf. From Premises (2015) The book in its entirety, an entirety that’s bound to lose and loosen its own identity through gigantic, wavelike rhythm, is thick with description, overwhelmingly so, but as such becomes successful through an achieved accessibility by its own curves. Narrative moments blend, blur, peak, bounce, and slap up against one another, and through a powerful proclamatory style that creates harmony between the macro and the micro, Enzensberger achieves a whispering peace. The book is fascinating in its array of lenses and magnitudes that are as scrupulous as they are forgettable. The interweaving and networking of the narrative are incredibly overwhelming in their highs and lows of ambiguity; a certain edgy value system dictates qualities of flow and tone but remains implicit as subtext. Who is Enzensberger in these diverse sequences of positioning, and where is there humanist connection, intimate conduction, and the overall action that undoubtedly draws in the reader? I felt compelled while reading this with the same emotional resonance of a quasi-serialized popular mystery novel, or Bolaño: that is, put simply, the effects result in a quirky unpredictable knowability, like the entering of a labyrinth, the approach toward a vivid landscape of walls with boundaries and growths and decays. Pushing forward while pressuring memory to uproot and upturn through reversal. It’s very hot and his guests are suffering in their dark suits. Our host invites us to go for a swim. He’d like to get into the water himself. His visitors haven’t brought bathing costumes with them. Shock, horror! What does protocol say? Some are at a loss what to do, others don’t feel like a swim. Can one take a dip in the nude, as the head of state suggests, and that in the presence of the author of The Second Sex? Most prefer to sit down on the steps, chatting cautiously, while our host disappears into one of the two bathing huts. Only Vigorelli, an unknown author and I feel like a swim. We get changed in the other hut where we find three pairs of oddly shabby bathing trunks laid out for our host and in his size. They come to our knees. I have to hold mine up with both hands. The 10 minutes I spent in the Black Sea were possibly the only comfortable ones of the day, for our host and for us. Only the bodyguard in his boat, ever-ready to save his master, showed any concern for our well-being. From Notes on a First Encounter with Russia (1963) As a person who did not live to see the Cold War, to see mythologized Soviet Russia, to see the tensions between the right and the left, between capitalism and communism and socialism, most of this book for me was a surprisingly enthralling experience looking at the lives of individuals overwhelmed and inundated with systems of rhetoric and resolution. From the sanctuary-esque Norway to the thrashingly on-edge Germany to the vast (endlessness) of Russia to the pressurized turbulence of Havana to the quaint USA, the world of the 6th and 7th decades of the 20th Century is one that is flourishing and fully realized by a man who lived through them. And exquisitely, Enzensberger did his share of living to reflect his share of writing. No landscape was left unexplored, and in this exploration there was a serious commitment to the detail in-betweens of each image. There exists an underlying empathy that is supported with both coordinated arrangement of people and sheer lists of descriptive information of the objects surrounding him. The presence and distribution of a thorough representation transformed this book from a spirited autobiographical description to a fantastical world. This hyper (hyperized?) realism, filled with trepidations and alleviations of truth, brings new faces to the world of unknown. Oddly, I think about Enzensberger taking on a role of relative neutrality and emotional responsibility that becomes offset through a degree of coldness from an intellectualism, and how what results contributes to an accessibility. Can such accessible writing, a production and a respectful body of compassion, expose greater waves of empathy that exist beyond (after) the text? The person is made from old newspapers that have been soaked and are then pressed into a hollow plaster mould and dried out. Once a day the mould is opened and the human being is born. It’s full of holes, fully grown, rough and empty. Brain and lungs, heart and spleen, bowels and sex organs are all missing. It’s open, hollow, unprepossessing; leading articles from the Party newspaper can be read on its skin. Then it’s scraped smooth and polished. At the next table a woman dips it in garish green paint: that’s the primer. Next an eerie pink is slapped on. From Memories of a Tumult “Tumult” is defined in Google as “a loud, confused noise, especially one caused by a large mass of people.” Oddly, and perhaps with slight irony, and perhaps with slight intention too, this book pauses before the realm of the “tumult” of which it is named. Following the granularity and texture of the world and its spectrum of perspectives and inspections, a greater thematic curve extends out of a unison of the sections of the book (reinforced by the poet’s interjections and reflections). The bursts of energy out of that curve tempts the levels of noise, the confusion, the booming, but there is a consistency of comfort through the breaking down of intensity by a strict, authorial control. As much as Enzensberger jokes about his work being distinctly Russian (he even mentions, in a blink, Dostoyevsky as one of the greatest writers), the book indeed blossoms into a quintessentially Russian mode. And, without being too self-aware of itself and its format, it does provide gentle critiques of systems that have previously and concurrently exist, fail, and continue to operate. Despite it all, human romance is what holds the author, and the life around him, together.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Welcome to Yellow Rabbits. Thanks for visiting.

All reviews by Greg Bem unless marked otherwise.

SearchYellow Rabbits Reviews

Archives by Month

August 2019

|