|

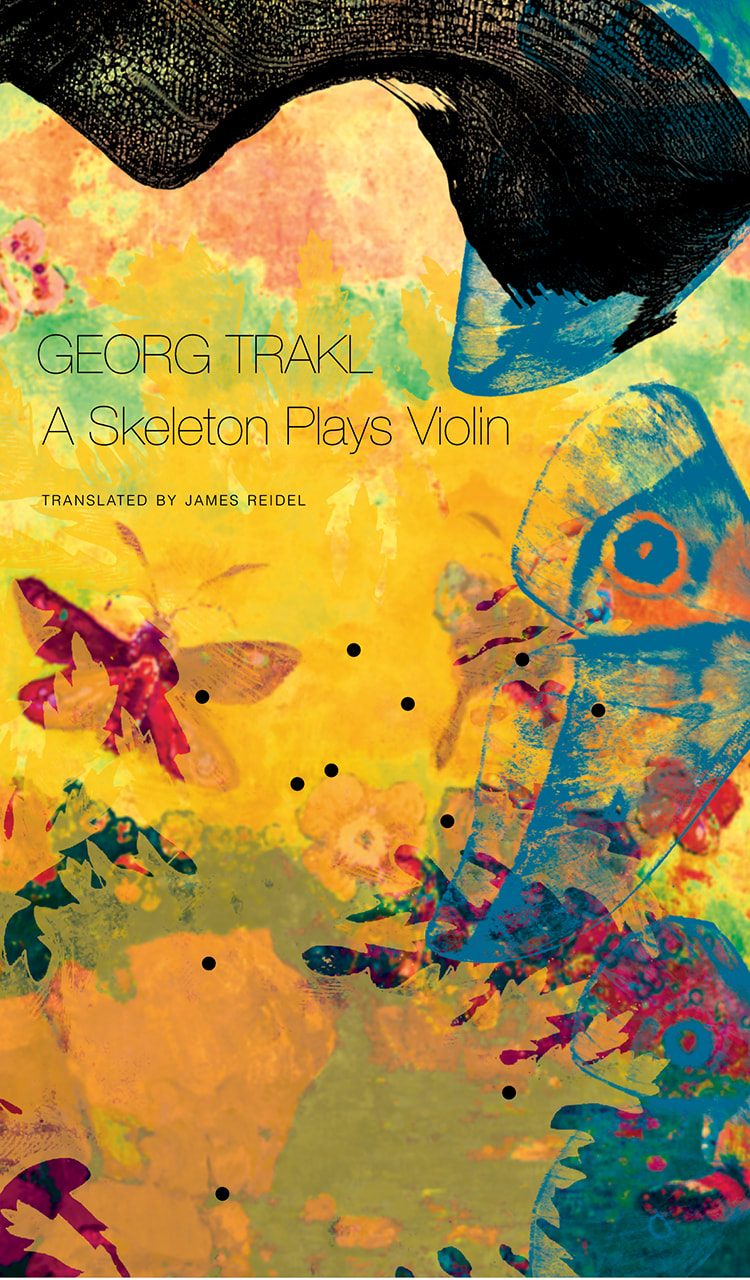

A Skeleton Plays Violin by Georg Trakl, Translated by James Reidel (Seagull Books, 2017)

Review by Greg Bem (@gregbem) “Georg Trakl (1887-1914) was born in Salzburg, Austria. As a teenager, he gravitated towards poetry, incest and drug addiction and published his first work by 1908, the year he went to Vienna to attend pharmacy school and became part of that city’s fin de siècle cultural life. He enjoyed early success and published his first book in 1913. A year later, he died of a cocaine overdose owing to battle fatigue and depression from the war-time delay of his second book.” “Shadows roll on the water with copper beeches and pines, and from the depths of the pond comes a dead, sad murmur. “Swans meander through the glimmering waters, slowly, unmoving, their slender necks rigidly held upwards. They snake on! Around the dying castle! Day in! Day out!” (from “Neglect” contained in the section “Published Prose and Poetry, 1906-1909”) The mountains of all of us, glass and otherwise, start and end with our creations, with our lasting imprints upon the known and unknown realities we find, or which find us. Through time that precedes and proceeds us, our act of creation, generally and minutely, becomes siphoned. There is the desire to find an underlying schism between what we have done and what we are. That many dissect the biographical only to discard it remains a triumph for life, and the life of the artist. And yet the contexts, the characterization, becomes an art in itself: that we might indelibly understand history of the artist and the artist’s world enmeshed is one of the pleasures and supreme functions of that same, contentious biography. I think often the biography is termed stale, or burdensome; a cruel act is to load upon our lives as the interpreter of the art itself the additional gate—both barricade and portal—of the life, and its subsequent, complementary death, of the owner of that creativity. The “Our Trakl” sequence from Seagull Books (which I’ve covered previously with the publication of parts one and two, Poems and Sebastian Dreaming) is not only a testament to the heavenly spiral of the biographic, and all that it can provide in weight and relief, but a re-envisioning of how that glass mountain may be perceived, in all its archetypal, quest-filled, damnation-evoked glory. The combination of the biographical research and the embodiment/imbuement of it within the text is incredible. I glanced and expressed the functionality of this twirl through the exploration of the first two volumes, though I did not realize the sheer romance and fatigue—the transcendence—as I do now, having read and taken to the fullest-extent-of-the-heart possible this third volume, A Skeleton Plays Violin. It is here, in this collection of beginnings, middles, and ends that we find Trakl’s work in its fullest flux. Trakl’s poetic shimmer, glazed with the harsh, cruel, complex, and fundamentally exposed life that we deserve to see is readily available now, and James Reidel, translator of all of the volumes, is responsible for providing this keystone moment, eclipse peak, edge of the forest. In this weepingly-full volume, we have Trakl in near totality. A rotting of dream-created paradises Blows around this mournful, lethargic heart, Which only drinks disgust from all which is sweet, And then bleeds itself out in vulgar pain. (from “To Slacken” in the section “Collation of 1909”) Pages turn and with them grow worlds, vastly colorful and vastly dissipating in a multitude of directions. The birth of the Trakl image and the death of the Trakl image are rooted in the organic actuality of a world beneath a God that has created, and in this creation, has the capacity for reflection, and refraction. So too is it with the poet. Trakl’s own light, his own writ upon the page, is as much a creation as it is a bound relationship. And then: an addressed biography, and its implications. From the earliest days dealing with familial scattering, disconnection, reinforcement, and reliance, Trakl’s work is crisp and brilliant, resolute and adolescent if only because of a certain waking quality to the poet’s ambiguous naivety. That is, the earlier work is confusingly mature, stark; it is filled with a strong language not fully punished by major loss and turmoil, and yet finds a degree of anchor and solace within quintessentially provocative images. The preservation-like effects of his earliest writing lead to early adulthood. It is here that is brought the rise of blood and formal education, exploration of vice, and the oft-related moments of incestuous, paradisiacal (and philosophically-explored) coexistence with a synchronous sister (Grete Trakl). This essence of relationship is paired well with a honed craft and an exacerbated sense of self. Selflessness arises through poem upon poem, through all seasons, by way of mimicking the vast literature at the young author’s disposal, and going beyond it into life and death at the doorstep. Greco-Romance mythology meets Judeo-Christian parables meets the foreground and background of the life lived in a pastoral-cum-urbanized Austria impended upon and upended by a hurried global industrialization. It is without doubt that Trakl’s emerging transformations serving as a crescendo lasting his entire, though short, adult life had a potent effect on the subsequent German Expressionism and other, more regional movements. There is a style, and a sensibility, which results from spiritually-confounded senses of juxtaposition and uproarious senses of reality’s cruel extremes. A branch sways me in the deep blue. In the mad autumn chaos of leaves Butterflies flicker, drunk and mad Axe strokes echo in the meadow. (from “Sunny Afternoon” in the section “Poems, 1909-1912”) A Skeleton Plays Violin continues on past the earliest moments into Trakl’s most intense sequences through a personal war of behavior, dissatisfaction, and addiction, and into a global war—the First World War, which leads to the poet’s final moments. And yet, as much as this trajectory is true, I write these words feeling guilty that I must leave out so many of the grimmer and brighter details. The romance. The political entwining with family members and confidantes. The close, filial bonds. The fraternity across distance and border. The madness of location and the security of reservation. There are themes upon themes within the epic A Skeleton Plays Violin that represent that most kaleidoscopic of spines we all face in the bodies of our lives, and to shy from them, as I must for the sake of brevity, does feel disingenuous to the nature of this fantastic volume. Still. I think about what is included. I think about what was written and how it has made its way forward through time. Near the end of the book, Reidel recounts a public, documented conversation from January 1914 Trakl held with another writer, Carl Dallago. The conversation begins with a point on Whitman, and leads to points on Christ and the Buddha, and later an editorial footnote raises the value of Dostoevsky in the poet’s life and beneath the poet's ideas. The initial conversation holds many meanings and is mostly is raised and concerned with sexuality and the belief systems commonly debated in an Austria very much grounded in Christianity; however, that earliest mentioning of Whitman, and the unfolding conversation’s exploratory nature evokes the indefatigable essence of Trakl as a writer. As compiled by Reidel, there is a way of knowing Trakl that has not been substantially provided to the contemporary English-language audience before this time—the versioning and relentless experimentation of our German-language poet is here in its textured, amorphous cherished state. Trakl, through a haunting perhaps only understood by himself, was masterfully engaged with language, including the language of the written, documented word that he created. As intimately seen throughout this book’s collection of many versions and iterations of the image, Trakl repeated, pulled, picked, and repurposed lines and poems in their entirety, and throughout various points in his life. A serialization of the self is the resulting image of this book as a whole, where Trak’s form is a form of exquisite, provocative, evolution that moves in multiple directions at once. It is phantasmagoria. It is thanks to the discipline and commitment of Reidel and the many others who have archived and connected the dots of Trakl's writing and life. Silent evening in wine. From the low rafters Fell a night moth, a nymph buried in blue sleep. In the yard the servant slaughters a lamb, the sweet smell of the blood Clouds our foreheads, the dark coolness of the well. The despair mourns dying asters, a golden voice in the wind. When night falls you will look at me with mouldering eyes, In blue stillness your cheeks fell into dust. (from “Psalm” in the section “Poems, 1912-1914”) To regress, let's take a moment to think of emotion. It is hard not to refer to the darkness that sits within Trakl’s core, a dimension that logically enters and exits the liveliness and deathly extremes of his behaviors. From early experimentation with chloroform to the mysterious death a la cocaine, Trakl’s pharmacological profundity is one that revolves, orbits even, the paradigm of the dim and the damned at the heart of his writing. There is the sense of loss and there is the sense of birth, and each one commits to the other. At times nihilistic, there is always the continued emergence and sustainment of morality and beauty, Trakl’s truest essence within his images, that bind the work together and also fail to bring the poet into a sense of complete abandonment, complete loss. There is hope. There is spiritual stability. And things remain complex from beginning, to middle, to end. This incredibly reality makes A Skeleton Plays Violin one book that is difficult and agonizingly affective in its embrace of the negative as much as the positive. For many, this poetry will bleed and bruise and blunder and capsize. It is murderous. It is tragic. But it is pure, to the point of Christ, in its reasoning with the spectrum of longing, suffering, and enduring we all must face in our existence. It is before, during, and after the essence of war. Perhaps the immediate environment leading to the global catastrophic war, paired with a familial history capable of incubating an extreme relationship with a precious sister was the perfect recipe for the resulting truths discovered and explored by George Trakl. Perhaps it was that and all the other grains of detail found within Reidel’s efforts. Regardless, the biography speaks these truths, reveals them, in tandem with the momentous quantities of writing that have been translated. And as such, we experience the extraordinary, the paralyzing. A writer of such capacity in such a short burst of existence is a writer of blinding awe. This text of the miscellaneous writings that filled the cracks of the glowing and striking void of Trakl’s existence, and “Our Trakl” as a whole, bears the capacity to convince us of this awe, and transform our own lives, our own biographies, in the process of creation. “Strange are the night paths of man. As I went forth sleepwalking in stone rooms and a small, still light burnt in each, a copper candlestick, and as I sank down freezing on the bed, once more her black shadow stood overhead, the stranger, and I silently hid my face in unhurried hands. The hyacinth bloomed blue at the window too and the old prayer pressed on the crimson lips of the breathing, from the eyelids fell crystal tears wept for this bitter world. In this hour during the death of my father, I was the white son. The night wind came from the hill in blue shivers, the dark lament of the mother, dying away again, and I saw the black hell in my heart; a minute of shimmering stillness. Quietly an unspeakable face emerged from a chalk wall—a dying youth—the beauty of some homecoming offspring. Moon-white the coolness of the stone surrounded the vigilant temple, the footsteps of the shadow faded on the ruined steps, a pink ring dance in the little garden.” (from “Revelation and Perdition” in the section “Published Prose and Poetry, 1913-1915”)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Welcome to Yellow Rabbits. Thanks for visiting.

All reviews by Greg Bem unless marked otherwise.

SearchYellow Rabbits Reviews

Archives by Month

August 2019

|