|

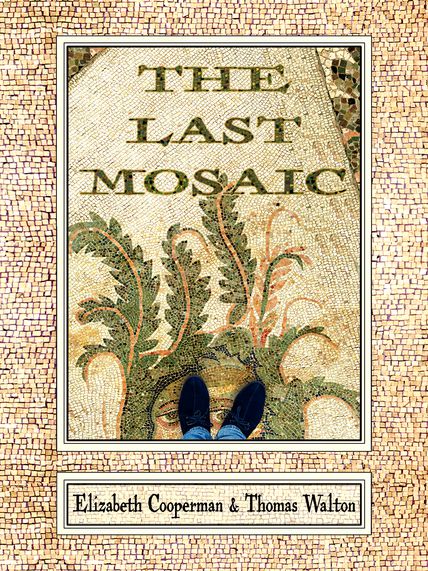

The Last Mosaic by Elizabeth Cooperman and Thomas Walton (Sagging Meniscus Press, 2018)

We love to think that various spaces are haunted, as we ourselves are haunted spaces. (from “Last Breath of Color”) The Last Mosaic is a collection of poetic statements and musing describing travels in Rome by poet-authors Elizabeth Cooperman and Thomas Walton. This collection is the first major collaboration between these two poets, and one that sticks timely as a footnote (or page rip or cobblestone trip) in the long history of representation of humankind. Like Anne Carson or David Shields (both who literally show up in the book in various ways, along with countless other authors and inspiring minds), the words in The Last Mosaic are loosely clumped into a scattering of ideas, linked together loosely into themes. In other words, the poems (or sub-collections) serve as clusters of revelation and insight and ultimately as documentation of Cooperman and Walton’s witness and conclusion during their time in Italy. The words, then, serve to help the reader navigate the behemoth of consequence and history consistently present throughout the Rome and its surroundings. The book’s a marvelous feat, one that swirls around mystically and temporally. It is filled with context and subtext, direction and floatation, movement and stasis, evidence and obscurity. Every poet knows that poets steal. Mimicry is the great device of art. (from “If We Replaced These Bodies with Our Bodies”) Most notably and superficially, the poets have written their book about their visits to Rome, and on the surface, in the moment, in the contemporary, it’s a beautiful and hearty record of the encounters in that multifaceted, multicultural place. The zoom that fills the spaces between each image, however, is on the historic and on the complex. In this case of world history, there is the act of borrowing and utilization that becomes key to understanding authorial placement. For Cooperman and Walton, it is a pleasant exchange between knowing the act of being present, and the act of engaging multiple pasts. Here, in “the last” space, we have an extension of all the previous ideas, a la mosaic, and an understanding that those previous ideas can be roped together in some finality. In this case, the finality of the authors and their presence. The train rattles south, sometimes wailing, kneeling through the Tuscan countryside heavy with sunflowers, olives, hayfields, gold scarves folding, rolling rows of grapevines running over the undulant soil to Rome, Rome where every square foot of earth has its mouth full of stone. (from "Little Scratches in Tempera") The writing, fueled by countless vibrations of space and time in Rome, maintains a poetic form of theft. Literary theft, not nearly as morally impermissible, as identified by the authors themselves, is a form of stealing done and done intentionally to amplify thematic range. It’s curious to see where and how that process is discovered; the usage and bringing in of the external forces, the peripheral muses of the city life that buzzes around our poets, is a usage at once amplified and also distorted by origins. It’s a curiously muffled and uncertain position for Cooperman and Walton to take, but as their other works have indicated, seriousness and play are required of one another to exist at all. The journey into the feathery soul and spinal juices of Rome and its streets and peoples and figures is a journey of intentionality but open-mindedness, and despite the rigid consistency of form (on the higher level) of The Last Mosaic and its writing, the flexibility of content is arousing and not nervous or tense. The process of the poets and their actions, here, in this publication, is complex; as we see them, as readers, these two authors move throughout streets and galleries and museums and plazas effortlessly, evanescently, floating about, taking and adapting that which initiates conversation and thematic development. The writing forms a keystone of imagery (their own ciphering, their own conjuration), ultimately forming images which serve to hold together (unlocking through an assumed completion or stability) the greater image. This bigger picture and macrocosmic lens of Rome is also allowed, through selection and exasperation alike, to be elevated more importantly than the smaller pictures contained within. At times. It’s not entirely clear just how much value is put on the small and the big throughout the book, and maybe it does not need to be. Perhaps the interplay between the various heights of Rome analogically indicates one step further how much beauty there is within the refractive, existential reality of a place set far into the past and far into the future at the same time. I did not see for fifteen minutes the trick of blood at the old man's waist training his white robes smocked in black velvet. (from "Soot on the Left Foot of God") As I read The Last Mosaic, not having my own geo-psychological or emotional relationship to that area of Italy, I watched as the authors established and set forth an arranged system of values and hierarchies of authority and autonomy by way of discovery. More summative, they bumbled along, lived lively moments, and etched their own interpretation of the world around them, much like the many great artists that have continued to occupy Rome for centuries and centuries and centuries. Excitingly, thus, The Last Mosaic with its self-awareness and conceptual core (whether identified before, during, or after the writers’ experiences) is a fundamentally challenging book of these bold and autobiographically-dependent poetic statements; its core, like the city’s reality, is deservedly process-oriented, obsessive of and through history, and maintains a quasi-permanent concept of an umbrella positioning in a world where anthropological deconstruction is gravely suggestive of truth. There is no feeling inherent in language. The poetry in language is what makes us feel. We use poetry all the time, though poems are generally thought to be useless. (from “Sick Bacchus”) Moments like the one described above from “Sick Bacchus” indicate a hearty and realistic relationship between Cooperman and Walton and the poems. Beliefs such as the poetry as synonymous with feeling ultimately identify and characterize the views of art throughout Rome and how we, as humans today, can integrate them into our own sense of being, by way of feeling. The book connects images, ideas, and ponderable frameworks (via strings and other logical progressions) thoughtfully, and again, intentionally. There is a rhythm and a pacing to the book as a whole that keeps it intact and even, in a sense of the eruptive, is capable of breaking down the poems themselves. Poem titles become earmarks but not requirements to the book’s truths. The book, like our occupations of space everywhere we go, is a testimony towards movement, and as such it doubles as a comment on the movement we physically endure and the movement of the language (representation) we express. Here, then, the book’s flow, a linear and circular (circuitously moving between both narrative identities) collection of moments and epiphanies, serves as binding to the reader. Sucked into the ancient vortex of story, hero, and the archaic, the reader has the chance to hold on and watch as that mosaic moves back into the ether time and time again in anti-conclusion. A resulting effect that the authors may or may not have intended is an understanding of the powers that come with the privilege to move, and the privilege to be able to see that movement throughout history. As the artist, the awareness of intention can be matched with inattention; what power we yield and how we relate to it, or refuse to. The book on its surface is often about embrace, but I encountered strands of denial and refusal within the book as well. Negative capability can be thought of as seeing without a code explaining things. That is, no political agenda. (from “Content as Costume Jewelery”) Cooperman and Walton, like Keats, hone for some time on this value of negative capability and perhaps the sentiments of anti-conclusion or anti-conclusiveness are simply synonymous with the understanding of bringing in that which can be brought in, regardless of motive and desire from the conscious poetic mind. On one-hand, that makes for an exciting immersion into an exotic or otherworldly space in a country not of one’s own; on the other hand, the post-engagement approach, as it might be gleaned, could be an active rejection of that momentary weight of being within the privileged hierarchy. The tourist, who occupies space and has the weight of reconciling that space, can be, through the ambivalent, serendipitous encounter, transformed into a more unified, contributing being, who can be held accountable for their presence in that space. A mosaic implies participation and contribution to the entire image, and not a denial, invisibility, or exclusivity away from that entire image. Despite their definite outsider qualities, Cooperman and Walton have done a fine job being “one” with the city of their occupation. While movement is incredibly important in this book, so is its inverse (as with any book of writing on the page). The Last Mosaic includes the gasps of presence and the nature of the authors and their conjoined, unified, and synchronic flow, as explored, but also in the injunction of description and stillness that pervades a world of movement, action, and space-time blossoming. Specifically, we have the “still life” poems, minutiae of encountered objects painted onto the page. For example, in “One Should Always Be Lost,” there is the following: “Up in the trees, a claw of half-dried leaves, arthritic, grabs a painful shock of sun. Purple wildflower clumps dance in circles around the gnarled trunks of olive trees.” While this moment, like many others in the book, is deeply personal and reveals a polish of emotion, there is the sense of the author displaced, channeling like Keats or, later, Spicer, the explosivity of the world that surrounds us all. In Rome, as demonstrated by our authors, there is a very pertinent sense of the natural as causing that channeling. Could the roots and new growth emerging between the mosaic’s tiles, atop the fresco, or, like the grotesque refuse of today’s living birds and humans, serve as that conducive sense to move beyond history? Beyond, in this case, does not imply a dimming or degradation of history; for the core of The Last Mosaic, it is the point and the ultimate purpose. But throughout, the reader is challenged by the authors and where they can find sense and grounding amidst flash upon flash of their inspiration. Whether it’s identifying the relatively quiet morning moments or discovering an absurdly extraordinary pool of turtles, these triggering moments are exquisitely spliced throughout the otherwise rhetorical and didactic process of the book. Beauty is that which we want to repeat. (from “If We Replaced These Bodies with Our Bodies”) Didacticism and history become key components to gauging where Cooperman and Walton may explore going forward. Living in Seattle, a place incredibly different from Rome in both respect to history and outlook to the future, the authors may have answers, at least in the form of poetry, that may be worth visiting from their home grounds. As a place that demolishes historical buildings for efficiency, cost, and value, there may be issues in understand that which can be provided by the beauty of repetition directly called upon by the authors in the quote above. As a city that, despite its best efforts, fails to deliver significant respect to the many cultures that fill it and recognize the recent but complex layers of the past, perhaps there is much to be applied or projected via The Last Mosaic. Still, the book does not concern Seattle so much as the splitting moment of existence that occurred in Rome during the period of its writing. There is no pressure to look beyond the book or move forward from Rome’s streets; the book feels as solidified and territorial as geography itself. And yet perhaps such concentration means its lessons, values, and themes can maintain their harmony and impact all the easier as readers who do or do not care about Rome will find out as they get carried from balconies to cafes to gardens to squares to waterfronts to arenas by way of Cooperman, Walton, and the countless other voices of the same literary vortex.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Welcome to Yellow Rabbits. Thanks for visiting.

All reviews by Greg Bem unless marked otherwise.

SearchYellow Rabbits Reviews

Archives by Month

August 2019

|