|

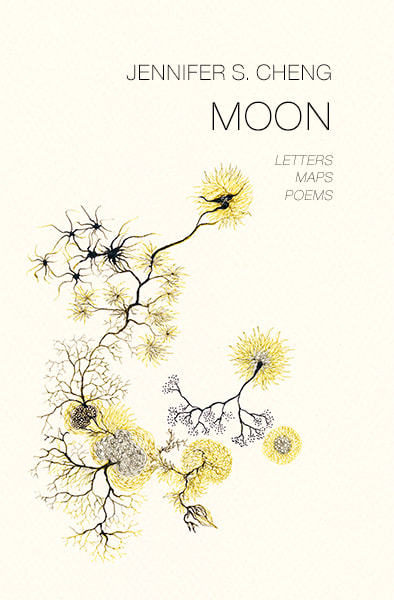

Moon: Letters, Maps, Poems by Jennifer S. Cheng (Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2018)

once she was crawling through a tunnel made of fabric unable to see the sky. to find a tear in the cloth, an eyelet of fear, which is to say, what is the body in transit? a pilgrimage-- (from “Her Dreams At Night”) The latest collection of writings from Jennifer S. Cheng comes by way of the illuminating and mythological Moon: Letters, Maps, Poems. Broken into a neatly layered and dauntingly dense five sections, a prelude, and an interlude, the book of poetry and prose draws upon a plethora of Chinese myths, most notably The Lady of the Moon, Chang’e, of which the book is named, but also including stories of Nü Wa, Tin Hau, and others. Moon represents an intelligent, matured phase of writing for the poet. Containing a mutuality of intellection and empathy, it follows its incredible predecessor, the acclaimed House A, which explored intimately the ether and disintegration of location, identity, homemaking, and familial lineage. To encounter Cheng’s newest work and ever-expanding relationship with the world via Moon is a beautifully transformative and profound reading experience. In Moon, Cheng’s words are incredibly inspired, fearless, and empowered by the fluctuations of that which surrounds her; and also, there is an integration and confidence that shows significant growth, appreciation, and resolve for the complexities of experience and endurance. Much like the Lady of the Moon, Chang’e, the proto-feminist archetype who is the subject of many ancient Chinese stories, Cheng is demonstrably capable of surviving, understanding, and acting against hardship and challenge and insight. This understanding of causation and achievement toward and of autonomy, both distinctly different and yet also bound in concept, inform many of the works and their monologues; these are writings of process, writings to embrace identity. Process and identity are significant themes throughout Cheng’s work, but here, in Moon, they are urged forward through the bold, unfaltering poet’s commitment and persistence to progress, knowledge, and freedom. Sometimes we begin as flood & gradually learn to shore. It is the process perhaps of looking at things alone. Unwoven, the body builds an altar loose, saturated in it (from “October”) Far from egotistical, the core divinity within these works represents a clear, sisterly (and, curiously, motherly) direction of empathy unrevealed so fully in previous works. Her previous movements in House A indicated a fascinating and inspiring relationship to space and the roots of home (as an idea and as an actualized, physical place with actual familial relationships and intimacies). In Moon, transition and migration are still very much resonating ideas; but they feel very much intentional and desirable. This intentionality and rational, firm placement is paired with the sense of wild and unknown that exists all around the poet. Between her homeland in San Francisco to her other homelands in Hong Kong and mainland China, to other, less-identified spaces, the reader is taken into the periphery of those authorial certainties. Environmental factors like heat and humidity trigger actions beyond the enveloping and into the charge of the writer: to find release and pace, to seek inward moments of reflection and protection. For me, the experience of seeing the poet leverage the awe of the myths and imbue a daily life of communication, work, and insight with those myths gives way to powerful moment of witness. The readers of Moon are granted great opportunities in encountering Cheng’s methodologies. Cheng’s work is heightened to the point of a ceaseless blend with the incredible and extraordinary, and yet we as contemporary humans need not find the old writings and storytelling to be completely beyond our current context. From bus stops to parks to apartments to boats to islands to marinas, the world is full of contexts that can and do mimic the archetypal. In other words, there is a precise, transcendental unity with history here. Cheng’s work pulls those strings, pulls out those ideas, merging them through her own turns along the path. When I read that the book contains “maps,” I became aware of the interpretation of the map as the abstract wayfinding moment contained within the beautiful truth of each poetic experience happening in the past and fortified through the act of writing: that what was still is, and vice versa. (If a closure of lines is always a lie. If shadows are multiple because the body is multiple. If, then, a continuation, the moon in its phases. Bewilderment and shelter, destruction and construction, unthreading as it rethreads, shedding as it collections.) (from “Prelude, part i.”) In some cases, these merges of old and new are most prophetically balanced by the image of the moon. As a symbol with an endless array of meanings, that which is lunar and orbiting in the fullest declaration of gravity serves the poet and the reader both with the energy of reflection. Astrologically haven-like, the moon is where Chang’e was made to be, to live, to continue, grown and growing, following transgression and complication. Cheng explores Chang’e’s movement to the moon and there are as many reasons why it was not Chang’e’s choice as there are reasons that she had to go. And yet, despite this ambiguity of positive or negative triggering acts that inspire Chang’e’s timeline and journey and resulting emotional circumstances, the effect of the movement to the moon, at least partially, is an embodying of the necessary learning, growth, and subsequent liberation. As hard as it was, and continues to be, from a remarkable number of angles and interpretations, this movement and relationship with the moon is still representing epiphany, insight, and progression. That moment of the epiphany, of the transformation by way of reflection and reaction, is balanced throughout the book, allowing the floods of verisimilitude to open and close like a hinge. Let me quarry the hemispheric drift Let me curdle the nightfall home (from “Creation Myth) The form of Moon offers another integration of truth. Its five sections indicate more qualities of mapping, trajectory, and an indication of that process towards reclaiming space for growth and independence. The book begins before the five sections with a prelude, “Sequesterings,” that is enormously enjoyable to read without any context of the mythologies of the book. It is abstract and abundantly self-sustaining, providing a splinter of what follows: “Iterations,” “Artifacts,” “Biography of Women in the Sea,” “Interlude: Weather Reports,” “Love Letters,” and “From the Voice of the Lady in the Moon.” The five sections, split with their interlude, each offer unique angles on the precision of Cheng’s experience. They serve as their own waypoints in the map, but also serve as individual maps of life and the Chinese mythos pulling in characters in some cases and leaving out characters in other cases. They are pillars, pylons, temples that create that visual boundary between the lines of thought that the poet traces. For as long as the stars do not seem to align in an orderly manner, as long as such lost light sources make their way into the spinning crevices of her lungs, she will continue to ask herself: How does one make a habitation of it? What is the relationship between a woman’s fragments and her desire for wholeness? (from “Chang ‘E”) Tracing is one of Cheng’s poetry’s best qualities, from my point of view. Being able to shift and create a poetics that contains both the exquisitely researched and the dutifully exploratory, as a representation of confidence (as opposed to anxiety, unsureness, and pretension), allows a floating essence throughout the book. Like her previous works, this engagement is deeply serious and focused, yet also open to that which is profound and that which is profoundly unexpected. As such, the book contains moments of surprise and delight; there were moments for me, as the average reader, where the book opened up and changed directions and followed leads, or took rests and pauses and meditations, and being within them as the reader felt secretive and empoweringly inspirational in its own way. In this spectra of Cheng’s poetics, the result is ecstatically authentic, ironically personal even when mythological, and awe-inducing. The book, it appears, is a gift being given to the readers just as it is a gift given to the poet. There is a sense of award and reconciliation contained within that floaty, tracing spirit that lingers within the pages. [. . .] if you take how she journeyed in utter silence, sailing in no particular direction across an endless and unbounded sea, dully lukewarm water melting into overcast sky, waiting for the waters to recede, waiting to land, somewhere, anywhere—you will remember, above all else, how she is—motherless, childless, godless-the last girl on earth—how the story of the world begins with her, a body in the marshes, sleeping, alone. (from “Nü Wa”) Despite one’s knowledge or lack of knowledge of the Chinese stories that are contained within Moon, the book is a significant next step for Cheng and a significant contribution to American poetry in general. It will, I’m sure, be recognized for its respect for an elevation of the adapted Lady of the Moon stories, inclusive of their feminist edge and elevation of the female spirit. The fascinating form and the revealing of Cheng’s continued growth and forward momentum as a writer are also worth noting again, as those who left House A will be amazed at where the poet exists in this work. And beyond all this context and these implications, the work stands on its own in stunning, absorptive independence. Like the reflection of the moon on a body of water, there is nothing quite like Moon, nor do I think there ever will be something like it by Jennifer S. Cheng or any other writer.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Welcome to Yellow Rabbits. Thanks for visiting.

All reviews by Greg Bem unless marked otherwise.

SearchYellow Rabbits Reviews

Archives by Month

August 2019

|