|

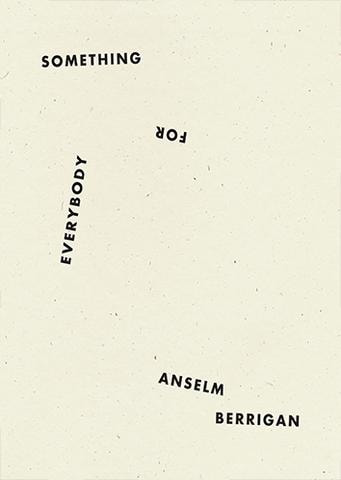

Something for Everybody by Anselm Berrigan (Wave Books, 2018)

May I have a sip of your cigarette, asleep in all my clothes, crying, uselessly, as your singularity apologizes for & preserves our long way around to an open muted slightly flittering love? (from “The Parliament of Reality”) The greatest act of truth in Anselm Berrigan’s eight book of poems, Something for Everybody, occurs in the book’s final piece. The poem, “& What Does ‘Need’ Mean?”, is a grotesque and grizzly ramble of a poem that shows Berrigan’s strongest and weakest qualities in its twelve pages. Those qualities, the poetic rampage and the incessant confessionalism, are seen intertwined and summate the otherwise messy and stale preceding contents of the book. In “& What Does ‘Need’ Mean?”, the reader encounters a dedication to and homage for St. Mark’s Church in New York, and it is here that the image of the center for the poet, the “downtown” brought into question through the poem’s concept (which was part of a generative, thematic exercise created by the Poetry Project, entitled “(Re)Defining Downtown” in 2016), is portrayed. Partway through the poem, Berrigan writes: “I keep going and coming / back to this place for that & by / the way, you do get, right, how / truly fucking strange, if ordinary / it is, to be breathing, here, doing / this with a voice?” The truth of this set of lines, arguably prose boxed in and controlled in the narrow columnar style the poet has mastered, is a truth revealing crisis. Berrigan’s poems breathe in and out, accepting and pushing past crisis upon crisis. These moments of urgency and dramatic interjection are often buried beneath circumstance and pure image. That the poems of Berrigan often appear to be haphazard journal entries, scrawls upon a palm or a page in the middle of a park or a train terminal, reflect the speed and directive of their creation and the poet’s processing. This is pure New York, in all its tragic, unending anti-glory. Then it was as if I didn’t speak for another year, & that’s a feeling, not another fucking metaphor. (from “& What Does ‘Need’ Mean?”) When I started reading Something for Everybody, I felt the tame, erratic tones of Berrigan that his previous seven books contain. The forms were slightly estranged and kaleidoscopic (and ironically-cum-disappointment there most likely isn’t something for “everybody” in the book), but otherwise this is Berrigan’s hallmark style, his calling card representation of the world once again butting and jutting its way into focus through “the book” format. This book, however, feels slightly worse, though, and by worse, it is good. It is mildly exciting, a mediocrity and extravagance at once, that demonstrates the flattened reality of New York City. It is, thus, sickening and necessary at the same time; a book I can hardly recommend anyone read but can feel confident and describing should someone care to read it. Earlier in the book, Berrigan has composed a list of “mini-essays” that are in the style of and taking the language from Joe Brainard. One essay struck me as an epitome of Berrigan’s structured gaze toward craft. “Turns” reads like this: “My work never turns out like I think it is going to. I start something. It turns into a big mess. And then I clear up the mess.” (From: “17 Mini-Essays on The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard.) Another piece of the puzzle in decoding, understanding, and learning to accept Anselm Berrigan and his barrage of bluster and agony is to understand his poems as rough patches that have been cleaned up. The poems, which combine the hackneyed influences of various generations of the New York School, language poets, beats, and other “poetry movements,” are poems that do much with too little. The poems are often directly derived from or referencing writers whose souls should be at rest but whose corpses and works continue to be dug up and sifted through. In our era of technology and movements towards equity, the result of this vacuous reliance upon the past is blustering and is agonizing. Just as The Poetry Project attempted to define its role in 2016 following the emergence of a new face of tyranny, there is an attempt for the poet to define his role too, using whatever is at his disposal. And yet, the disposing act never quite makes it, as we spin, and spin, and spin through 20th Century Poetics. That said, Berrigan is a family man who brings his family into the poems, just as he brings the outside world into his poems, and this interconnected, networked self contains some saving graces. The most brittle act of antiquated New York poetry is juxtaposed with (or, forgivingly, balanced by) interposed moments of the now, the new, and the emerging (“Tap for more tweets, munch / In the preserved meatlight” goes “Inward Branding Mechanism 2: Lonesome Sabotage”). Perhaps a comment on the antiquity of New York as a place and idea more than Berrigan as a poet following and honoring various lineages, every fresh image and idea related to contemporary communication and information exchange in the United States often gets dwarfed by pigeons and decaying train lines that have little to no relevance beyond themselves and the New Yorker devotees that may or may not identify with them to the degree we find Berrigan identifying. Those moments of tweets and social media, of the web, of current socio-political phenomenon are absurdly dim and overpowered by the vortex of New York and the faceless urban living that so many New York poets have described again, and again, and again. This obsession or trap or fate is not new for Berrigan, as any reader of his would expect, and its descriptions are important if only to serve as footnote. This is what’s going on over there in New York. The loop continues. Hurrah, hurrah. for the nod out in collaboration with medical relocation I’m always a touch late to ten baroque minutes away from a bad repair job in gravel kittywalks where unnameable fluidity unlimited only by the flow of your distressed clarity of material (from “Asheville”) My criticism on the most important city in the world aside, the poems in this particular collection have plenty of shining moments that any poet actively studying and pursuing poetry would benefit from engaging. From “Speech,” a light concept piece containing four words (“SMASH THEM. / EAT THEM.”) to the typically morbid and self-/society-defeating “To a Copy” that scrolls down the page like a spiraled staircase, “Nothing / gets to be real / or realized / or reality-based / or filmed as if happening / or rendered realistically / or branded contemporary / or performed spontaneously” (and so on), the poems range wildly as per the book’s name-sake. And often the language does appear sparking and vaguely refreshing. But then there is the constant mess, and the jumble, and the shrouds of tones that inspire a feeling of decay and disrepair. Halfway through the book, I found myself feeling a reminiscence of depression, a weight of the ugly and relentless machine: poetry as chore, as weight, as grumble. Most of Berrigan’s poems, when not fuddling through tricks in phrasing and lingual aerobics, are often situated as pure exhaust. The poet is shuffling around in a sea of images that carry as much meaning as breathing. And the breathing is for the poet, not the reader. So what is the point of these poems for the reader? I return to this question time and time again throughout the book. For example, I ask it when I see “June at One on Ave A,” which reads: “Bus! / Bus! / O bus. . . . .” the text falling down the page, like a dull, pseudo-apocalyptic nightmare. Similarly, I ask about intention and affect when I read the long blocks of text in “New Note” that can’t help me sigh with more exhaustion. The text is composed in huge paragraphs that could just as easily be pages and pages of columns, but it perhaps doesn’t matter. There is a resulting nihilism as I read “the song’s importance retelling what you’ve witnessed undersea, out windows at declines” . . . which has its own, rusty charm. Perhaps Berrigan’s calling card, then, is a sorrow that can now be quintessentially branded into a fetish. This poetics is a poetics of industrialized pity, meeting mechanized repression, and a holistically-realistic essence of mental illness intersecting with blinding flashes of awe. Thanks to language, of course. And thanks to today’s undead: a bleached, ruptured Americana beyond and yet bound to the mind. And that is truth, a single man’s truth, who haunts the streets and histories of New York, and continues to document his own, regardless of the implications and disastrous messes to be made.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Welcome to Yellow Rabbits. Thanks for visiting.

All reviews by Greg Bem unless marked otherwise.

SearchYellow Rabbits Reviews

Archives by Month

August 2019

|